Fairytale Project

June 3rd 2011-2014

Slought Foundation, Philadelphia, USA

In 2011, Ai Weiwei, Aaron Levy, and Melissa Karmen Lee collaborated on a research project revisiting Fairytale. We created an online archive which involved translating and selecting primary materials such as participant questionnaires, snapshots, and recorded interviews that Ai and his studio conducted with the one thousand and one Fairytale participants over the course of the project. The translation process of these primary materials were predominantly accomplished through a global volunteer network and could be found at Fairytale Project, the website archive conceived for the project. In the spirit of international collaboration and audience crowdsourcing, we also created an online translation kit, which was made readily available for participants from all around the world to download and for teachers to instruct in their classes, at home, or create their own translation groups. Of particular interest to us were the experiences, memories, and understanding of how the participants themselves reflexively interpreted their participation on the fifth anniversary of the project in 2012.

There were three stages of interviews: the questionnaire that all participants filled out before Fairytale, fifty-six participants that were interviewed in depth during Fairytale and finally, the Fairytale Project interviews which we conducted in the third stage of our research, where we contacted over six hundred participants and interviewed approximately one hundred people. These three stages of interviews explored different phases of reflection, which depended on the Fairytale participant’s reflexive analysis of past events that they shared with us as researchers and Ai’s studio assistants. All participants were given a camera, a usb drive to upload pictures, and encouraged to record their ongoing travel experience, resulting in the creation of the present stories of their lives during the duration of Fairytale. Many of the Fairytale participants’ experiences such as their first time on an airplane, exploring Kassel, Germany, meeting local German villagers, experiencing the Kassel countryside were all extensively documented in photography and video by the one thousand and one Fairytale participants that were experiencing it firsthand.

The third stage of interviews were conducted during Fairytale Project and were deliberately executed late in the project as we anticipated that the longer the time gap, the more significant it would be to how people’s lives had fostered change and growth. We were exploring questions such as: how does an artwork affect people’s lives, particularly key people that became a part of the art? Does their participating in the artwork resonate with an impact on them later in life? To elaborate further, in three to four years, the impact of a travel experience and an art project may not have the fully recognized significance that might take seven to eight years to manifest itself. Equally, the lack of the artwork affecting anyone after seven to eight years also had it’s own significance. The Fairytale Project’s aims were to reflectively look back at Fairytale to explore the participant’s lives (in 2007 through the study of the empirical material questionnaires, photos and documents), compared to 2012 present day research archive time. The interviews (beginning of the project, during and afterwards) in Fairytale and Fairytale Project acted as a narrative mode of processing identity transformation across time and place, which animate all the examples that I plan on discussing in the dissertation.

Our 2011 Fairytale Project created new iterations questioning and interrogating the main artwork. Fairytale Project’s purpose was to evaluate, reassess and critically understand the relational concerns of Fairytale the artwork by re-interviewing the participants as subjects, attempting to reflectively understand and engage with their past (and present selves) as subjects in the project. The re-interview process was also a performative element in which we hoped to understand the parameters, borders, and differences that constituted the artwork and the archive. There was a performativity in the way that we self-consciously went back to re-interview the same participants. In a 2007 interview with Natalie Colonello, Ai has said

‘I think that past and future, these two realities which are both internal and external to each person, are all integrated in very different forms and possibilities that make each individual unique. (Colonnello, 2007)[1]

In Fairytale, and The Fairytale Project, we explore the past and present of each individual participant’s lives over a duration of ten years from the beginning of the project 2007 to the end in 2017.

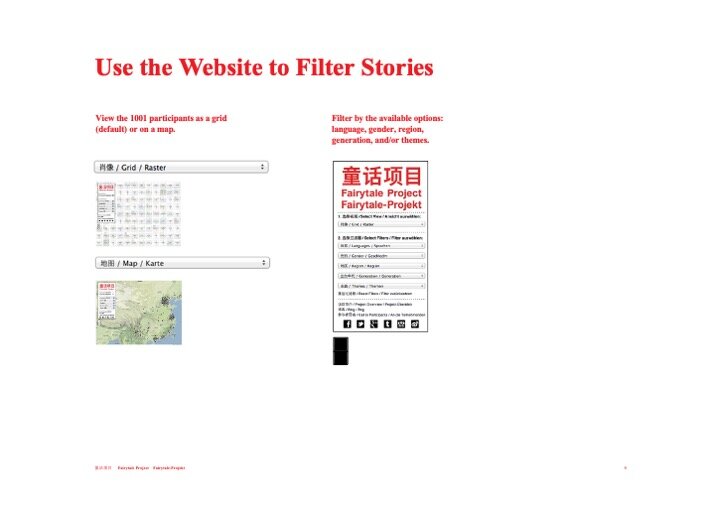

Fairytale Project included the following components: archival material gathering, volunteer translation, and finally, the re-interview process of the original participants that took place a period of five years later encompassing translation projects. The decision to structure Fairytale Project as an archive instead of an exhibition was made due to the majority of the project involving research and examination of historical documents, elements of this analysis which had more archive-like characteristics rather than a display or presentation of objects which would fall into the category of an exhibition. We explored this in-betweenness of an archive and exhibition by presenting our ‘archive in process’ at an exhibition at Slought Foundation in 2011.

Ultimately, Fairytale is a political work about nationhood and border control or artistic question about migration of fiction and global myth.

Fairytale Project, although in its appearance and outward form resembles an archive, contains much more than a historical examination or collection of records and documents. One example of how Fairytale Project differs from a traditional archive is that the second phase of the project had a strong participatory component, including a living volunteer community of crowd sourced translators who playfully interact with the text by translating the Chinese written interviews into English online on a daily/weekly regular basis. On a daily basis, translators would contact us and begin translating documents in which we would upload, incrementally adding to the people that were able to read the text online in English, Mandarin, and German. Fairytale participants were also contacted individually through a laborious process of checking old contacts of telephone numbers and postal mailing addresses. Those original participants that we were able to reach responded in a variety of different ways. Some were glad to speak and reminisce about their time abroad, others seemed guarded as to why we were re-establishing contact and reiterated that there was little to no impact on their lives.

[1] Natalie Colonello, ‘1=1000. An Interview with Ai Weiwei’, August 10th 2007 ’ https://blogs.artdesign.unsw.edu.au/artwrite/?p=610

Related Book

Ai Weiwei: Fairytale, a Reader

Press Coverage